50 shades of gay I wanted to be brief. I wanted

to be simple. 50 may not be enough. My definition of gay is the

entire spectrum between the extremes of

male and female. Each axis in the spectrum will

be descriptions of the physical, mental,

emotional and psychological aspect. Along the way we will pass

through some naming conventions. In the LGBTQ spectrum of

classifications the assumption by society

is that this constitutes about 10% of the

human population. Each letter represents

an attitude of self-identity. The prefixes

Homo and Hetero refer to the sameness or

opposite characteristics of attraction. Homo means same, such as two

males or two females attracted to each

other. Hetero means opposite, such as

male and female attraction. Anti-or just the letter a is a prefix that

means "not". Examples in the English

language would be antisocial and asexual. Bi is a prefix indicating two,

indicating a person might demonstrate

characteristics of the two main features.

A person might feel attraction to either

sex or gender. Mono is a prefix for one and

only one. partner

you would be connected to either by

marriage or emotional agreement. Example:

monogamous, meaning only one partner. Poly is a prefix meaning two or

more. Example: polygamous or poly amorous. Phobe

or phobic is the syllable that denotes

fear, hate or uneasy association. Examples homophobic. Lesbo

refers to the mythical island in the A siren was a fictional female

creature that could seduce men by their

melodious singing. They were thought to be

irresistible therefore sailors crashed the

boats against the rocks trying to draw

close. Amazon is the term used to

describe warrior type women. In ancient

days they removed one of their breasts in

order to be more proficient with a bow and

arrow. In modern days a woman might be

called Amazon if she were powerful and

aggressive. Q is for questioning. This

starts in early childhood and can extend

the lifespan of an individual. It is the

most perplexing during puberty and at

those times in a person's milestones when

rethinking your purpose in life may be in

question. Trans is for transitional. It is

the most complex to comprehend as it

defies definition. I did meet a classic

transsexual in my life who was able to

articulate all the possibilities and wrote

a very interesting paper to her physician

and counselor. She has expressed to me

that she does not like the transsexual

community because they are intent and

trying to make her conform to a sameness that she

rejects. In order to give you an example

of how she names the phases of her

identity, she was born in What's

in a name? In many societies getting a new

name fixes a lot of stuff. A female can

take the last name of her husband.

Children may add the suffix to their name

indicating their age in the community.

Examples are John versus Johnny, Tom or

Thomas versus Thomasito

or Tommy. The whole spectrum of nicknames

can be self-induced or foisted upon by

friends or enemies. When my trans friend begin

to identify herself as a Jew, she

requested the name "Shosha",

which has a Hebrew meaning. She was a

Russian, American, male/female

transitioning Jew who only had to cut her

hair in an androgynous fashion to be

properly acceptable to anybody in any

community. I think she pulled it off in a

grand fashion. She can sit or stand it any

crowd and nobody comes up as high as her

shoulders. Her external clues for gender

are by the way she walks and talks and

sings. Her smile is her best calling card. In order to

go further with going to have to get

physical. The following clip is from

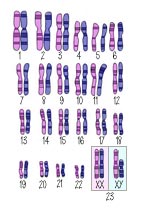

this link: http://www.ingender.com/gender-info/conception2.aspx The main event of

conception is the uniting of the mother

and father's chromosomes to form a new,

unique human being. Let's delve into the

fascinating world of your chromosomes. All

of your body's cells contain chromosomes,

which are packages of DNA strands; DNA

holds the map of your genes. If you're a

human, 46 is the magic number: we have

46 chromosomes, in 23 matched pairs. One

chromosome in each pair was contributed

by your father, and one by your mother.

Every cell in your body contains your

complete genetic blueprint, or

your genome, in the 46

chromosomes in its nucleus. A sex cell (egg or

sperm), however, is an exception. Rather

than a complete set of 23 pairs of

chromosomes, an egg or sperm has only

23 single chromosomes.

When the two unite, the chromosomes

combine, giving the new cell the proper

number of 46 chromosomes. Take a look at

the 46 chromosomes in one of your

normal cells (not an egg or sperm).

What a chromosome actually "looks

like" is a complicated question, but

we can represent them kind of like

this: Some

chromosomes are larger than others,

because they contain more DNA. All

chromosomes are part of a matched

pair, one from your mother, and one

from your father (which I illustrated

here by coloring them pink and blue).

The pair is "matched" because they

contain the same genes -- for example,

both of your parents contributed a

gene for eye color, and of the color

of your eyes depends

on which gene is dominant. The

Sex Chromosome: XX or XY The

last chromosome is different. It's

called the sex chromosome, and it

determines whether you are female or

male. If you're female, we call this

chromosome XX, and as you can see, it

is a nicely matched pair like the rest

of the chromosomes. If

you're male, the last pair of

chromosomes is called XY, and they're

not a matched pair. The X chromosome,

contributed by the mother, matches

up with a much smaller Y chromosome

contributed by the father.

For reasons that aren't fully

understood, the X chromosome contains

far more genetic material than the Y,

and thus it is larger in size. In

2003, the Y chromosome made headlines around

the world when it was mapped by

the Human Genome Project. Oocyte Now

take a look at the chromosomes in an

egg. We see only half of the usual

number of chromosomes. Why didn't I

color these chromosomes pink, since

they all come from the mother? The

answer is that the mother doesn't just

pass along a copy of the chromosomes

she received from her mother, but new,

unique chromosomes that contain a

mixture of the genes from both of her

parents, ensuring that each oocyte, and

each child, is genetically unique. Notice

that the last chromosome, #23, is the

big X chromosome. Because the mother's

own 23rd chromosome is XX, the egg's

23rd chromosome must always also be an

X, because the mother only has X's to

contribute. So any egg can become a

baby boy or a baby girl, depending on

whether the father's sperm contributes

an X or a Y to pair with the mother's

X. Here

are our friends the chromosomes again,

this time from a sperm. And again,

these chromosomes aren't a copy of any

of the man's original chromosomes, but

a unique mixture derived from each

pair, bestowing traits from both of

his parents to each sperm, and thus to

each child. Notice

that the last chromosome, the sex

chromosome, is either an X or a Y in a

sperm cell. This is possible because a

man has an XY pair as his own 23rd

chromosome, so a choice is possible

when a sperm cell is formed. Technically,

I should call the two types of sperm

"X-chromosome-bearing spermatazoa"

and "Y-chromosome-bearing spermatazoa",

but I always just say X-sperm and

Y-sperm. If

all this talk has put you into a

chromosomal coma, wake up! This next

part will be on the quiz. It

seems reasonable to think that if some

men only have sons, they may only have

Y sperm, or that fathers with all

girls might have only X sperm. But in

fact, years of testing have shown that

virtually all men have a nearly equal

number of X and Y sperm -- even men

who have fathered only boys or girls. The

explanation for this is that the

process by which sperm are formed -- spermatogenesis -- guarantees

that an equal number of X and Y-sperm

are produced. This is because X-sperm

and Y-sperm aren't manufactured

separately, but result from the

division of an XY parent cell. Normal

cells in your body are reproducing all

the time, by a process called mitosis: the

cell's DNA replicates (makes an exact

copy of itself), then divides down the

middle, resulting in two cells that

are identical to the original cell.

Remember seeing cells divide in

biology class? This

process of mitosis won't work for

creating sperm cells,though,

because sperm cells are special in two

ways. First, they have only half the

usual number of chromosomes. And

second, they're each genetically

unique, not exact copies like normal

cells. (If sperm and egg cells were

just identical copies, all of a

couple's offspring would be clones of

each other.) The

answer is a specialized form of cell

division called meiosis, used

only in the formation of sperm cells

(spermatogenesis) and oocytes (oogenesis). In

the testes, sperm is produced by cells

called spermatagonium. These cells

reproduce themselves in the usual way,

by mitosis, so that a man doesn't run

out of them; after all, he'll be

producing sperm his entire life,

starting from puberty. But

some spermatagonia

will undergo meiosis, in which a

single spermatagonium

divides into not two, but four sperm

cells. Here's an overview of what

happens (this is the good part): At

first, the cell has the normal 46

chromosomes, scattered around the cell

nucleus. (Pretend that the 6

chromosomes I've shown here are

actually all 46. Pink chromosomes come

from mom, blue from dad.) The

chromosome's DNA replicates itself

(shown by the 2 black lines inside

each blob in the picture). The cell

still has the normal number of 46

chromosomes, but twice the DNA. So

far, this is just like what happens

during normal mitosis, but something

new is about to happen. The

chromosomes next match themselves up

in corresponding pairs, the only

occasion they do so. Because this is a

man, of course chromosome pair #23 is

XY. (Again, you can pretend that pairs

3 through 22 are also shown here.) Chromosome

pairs exchange sections of DNA between

themselves, in a process called crossover, thus

mixing up genes from both parents. We

now have new, unique chromosomes. The

cell divides! The new cells have 23

chromosomes each, and the genetic code

is further shuffled by mixing and

matching chromosomes into the new

cells. One cell must get the X, and

the other the Y, from the 23rd

chromosome of the parent cell. The

new cells have the right number of

chromosomes for a sperm cell, but

still twice the DNA (from the

replication at the beginning). So... Each

cell divides yet again, yeilding two

X's and two Y's. Called spermatids, these little

round cells will develop a midpiece and

flagellum on their way to becoming

mature sperm cells: 2 X-sperms, and 2

Y-sperms. This

whole process takes about 74 days, but

don't worry that there won't be any

sperm ready on the big day --

thousands of sperm mature every

second. The birds, bees and

mules Horses

and asses have a different chromosome

count. Crossbreeding the two animals

produces a mule, completely different

from either one of those that made up

the mixture. But,

to understand why this is a problem,

we need to understand how sperm and

eggs are made. And to understand that,

we need to go into a bit more detail

about chromosomes. Remember,

we have two copies of each of our

chromosomes -- one from mom and one

from dad. This means we have two

copies of chromosome 1, two copies of

chromosome 2, etc. However, this isn't

entirely true for the mules. The

mule has a set of horse chromosomes

from its mom. And

a set of donkey ones from its dad. These

chromosomes aren't really matched sets

like in a horse, a donkey, or a

person. In these cases, a chromosome 1

is very similar to another chromosome

1. It looks pretty much the same and

has nearly the same set of A's, G's,

T's and C's. For example, two human

chromosome 1's differ only every 1000

letters or so. But

a donkey chromosome doesn't

necessarily look like a horse one. And

the poor mule even has an unmatched

horse chromosome just sitting there. To

make a sperm or an egg, cells need to

do something called meiosis. The idea

behind meiosis is to get one copy of

each chromosome into the sperm or egg. For

example, let's focus on chromosome 1.

Like I said, we have one from mom and

one from dad. At the end of meiosis,

the sperm or egg has either mom's or

dad's chromosome 1. Not both. This

process requires two things. First,

the chromosomes have to look pretty

similar, meaning they are about the

same size and have the same

information. This will have to do with

how well they match up during meiosis. And

second, at a later critical stage,

there has to be four of each kind of

chromosome. Neither of these can

happen completely with a mule. Let's

take a closer look at meiosis to see

why this is. The first step in meiosis

is that all of the chromosomes make

copies of themselves. No problem

here...a mule cell can pull this off

just fine. So

now we have a cell with 63 doubled

chromosomes. It is the next step that

causes the real problem. In

the next step, all the same

chromosomes need to match up in a very

particular way. So, the four chromosome 1's

all need to line up together. But this

can't happen in a mule very well. Like

I said, a donkey and a horse

chromosome aren't necessarily similar

enough to match up. Add to this the

unmatched chromosome and you have a

real problem. The chromosomes can't

find their partners and this causes

the sperm and eggs not to get made. So

this is a big reason for a mule being

sterile. But how is the silly thing

alive at all? Well,

there are a couple of reasons. First,

having an odd number of chromosomes

doesn't matter for every day life. A

mule's cells can divide and make new

cells just fine. Which is important

considering a mule went from 1 cell to

trillions of them! Chromosomes

sort differently in regular cells than

they do in sperm and eggs. Regular

cells (called somatic cells) use a

process called mitosis. Mitosis

is like the first step of meiosis. The

chromosomes all make copies of

themselves. But instead of matching

up, they just sort into two new cells.

So for the mule, each cell ends up

with 63 chromosomes. No matching needs

to happen. And our lone horse

chromosome is fine. The

other reason a mule is alive is that

nothing on the extra or missing

chromosome causes it any harm. This

seems obvious at first except that

usually having extra DNA causes severe

problems. In people, extra chromosomes

usually result in miscarriages.

Sometimes though, a child can survive

with an extra chromosome. For

example, people with an extra

chromosome 21 have Down syndrome.

Having all of the extra genes on that

extra copy of chromosome 21 cause the

symptoms associated with Down

syndrome. So

having extra chromosomes often leads

to real problems. But the mule is by

and large OK. The

extra genes must not be that big a

deal for the mule. In other words, the

extra genes on the horse chromosome do

not cause problems for the every day

life of a mule. So

mules are sterile because horse and

donkey chromosomes are just too

different. But they are alive because

horse and donkey chromosomes are

similar enough to mate.

Chromosomes:

Your Genetic Blueprint

23 Chromosome Pairs

Chromosomes

in the Egg

23 Single ChromosomesChromosomes

in the Sperm

Sperm

23 Single ChromosomesSpermatogenesis:

Equal

X's and Y's For All!

A mule gets 32 horse

chromosomes from mom and 31 donkey

chromosomes from dad for a total of 63

chromosomes. (A horse has 64 chromosomes

and a donkey has 62).A horse and a

donkey can have kids. A male horse and a

female donkey have a hinny. A female

horse and a male donkey have a mule.

A mule gets 32 horse

chromosomes from mom and 31 donkey

chromosomes from dad for a total of 63

chromosomes. (A horse has 64 chromosomes

and a donkey has 62).A horse and a

donkey can have kids. A male horse and a

female donkey have a hinny. A female

horse and a male donkey have a mule.