The Early Years

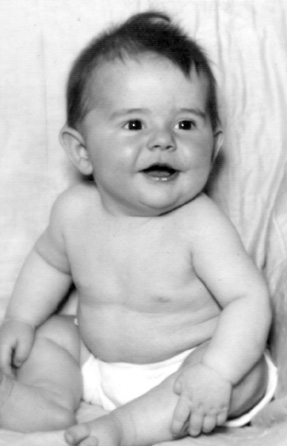

I was born

in the middle years of the Great Depression. It was years later that I

discovered what that meant. I was the first of four boys born to a blue

collar

family.

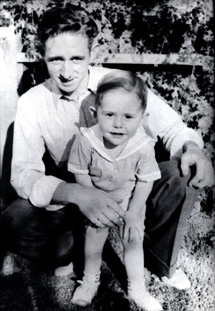

My

father

worked for the railroad in El Paso, Texas. He had an eighth grade

education and

was completing an apprenticeship as a machinist. He was skilled at

forming

metal with a lathe and milling machine. I can remember the smell of his

work.

It was the smell of oil in his clothes and the balls of ‘waste’ he used

to

clean his hands. Waste was the scraps from the cotton mills made up of

tangled

threads and scraps of cloth left from the looms and sewing machines in

the

factories. I remember staring at those mysterious balls of thread and

wondering

about the colors and how it was these threads were discarded before

they could

be shirts or dresses. What a waste. It was one of my early concepts.

My

father

worked for the railroad in El Paso, Texas. He had an eighth grade

education and

was completing an apprenticeship as a machinist. He was skilled at

forming

metal with a lathe and milling machine. I can remember the smell of his

work.

It was the smell of oil in his clothes and the balls of ‘waste’ he used

to

clean his hands. Waste was the scraps from the cotton mills made up of

tangled

threads and scraps of cloth left from the looms and sewing machines in

the

factories. I remember staring at those mysterious balls of thread and

wondering

about the colors and how it was these threads were discarded before

they could

be shirts or dresses. What a waste. It was one of my early concepts.

I remember

eating outside. There were picnics in open spaces and in the mountains,

made

possible by the fact that Dad only worked three days a week. Jobs were

so

scarce that workers would share a six-day-a-week job. It must have been

like

paradise to work three days and then have four days off. This was far

different

than I would experience later on with my own family. Later, Dad told me

what he

did. He cut up railroad cars and shipped them to Japan where the

Japanese made

weapons to make war on us. We would need that iron later to launch our

defenses

for World War II.

My

folks were very frugal. They took out a

mortgage and bought a house when I was about three. They bought a Model

A Ford

Coupe with a rumble seat; which I had fond memories of. I was allowed

to play

in and on the car and took great delight in driving it in my mind. A rumble

seat, for the benefit of anyone younger than I, was a compartment where

the

rear trunk is on a modern car that hinged from the bottom and revealed

an

outside bench seat for those passengers that did not fit in the front

seat.

There was a running board; which was a place to stand on the outside of

the

car, and footsteps up the back fender for climbing into the rumble

seat. A

Coupe could seat three adults that were not afraid to touch one another

or two

adults and one squirming kid. The rumble seat was only useful in dry

weather;

which was most of the time in El Paso. There were one or two spare

tires. One

spare tire was kept in an open well of the front fender and the other

hung on

the back of the rumble seat. The reason I was safe playing in the car

was that

it had to be cranked to start it and that took a very strong man like

my

father.

My

folks were very frugal. They took out a

mortgage and bought a house when I was about three. They bought a Model

A Ford

Coupe with a rumble seat; which I had fond memories of. I was allowed

to play

in and on the car and took great delight in driving it in my mind. A rumble

seat, for the benefit of anyone younger than I, was a compartment where

the

rear trunk is on a modern car that hinged from the bottom and revealed

an

outside bench seat for those passengers that did not fit in the front

seat.

There was a running board; which was a place to stand on the outside of

the

car, and footsteps up the back fender for climbing into the rumble

seat. A

Coupe could seat three adults that were not afraid to touch one another

or two

adults and one squirming kid. The rumble seat was only useful in dry

weather;

which was most of the time in El Paso. There were one or two spare

tires. One

spare tire was kept in an open well of the front fender and the other

hung on

the back of the rumble seat. The reason I was safe playing in the car

was that

it had to be cranked to start it and that took a very strong man like

my

father.

Life

changed on December 7, 1941. I was six and in kindergarten; and a radio

was

brought into the room so we could hear President Roosevelt. Radio was a

big

part of life at that time. Everything stopped and we paid attention

when the

radio was on. This time the teachers were very serious and we tried

hard to

understand about Pearl Harbor and the Japanese. I had heard H. V.

Kaltinborn

talk on the radio about the Germans in Poland but I didn’t understand

how it

affected us. My world was very small then and I didn’t understand about

nationalities or any place but El Paso. From that point onward my

education was

controlled by the events of the world.

I was

signed up for violin lessons and had taken several lessons from a stern

man

with a bald head. My dad and grandfather had lots of hair so I would

notice

that. After a few lessons I was introduced to a big room full of kids

playing

all manner of instruments. The leader said, “Give me a G.” I didn’t

have a

clue. That day was the last time I saw the bald man. I asked my mother

what

happened to him and she just said, “He was a German.” There were no

more violin

lessons. Some things are not explainable to a young boy. I was

beginning a new

education.

Fraternal

orders were big then. Mother had signed us up for the Woodmen of the

World. It

was like an insurance company. You paid your dues and had a small

insurance

policy in your name. You also went to a meeting hall and wore a cap

like a

soldier’s cap and marched to the music. A woman had a clapper made from

four

castanets on a stick and kept time even when there was no music. I

still

remember the marches, All American

Promenade, Over the

Waves and some Souza

marches that were played on a 78 rpm record player. We marched in

patterns of

columns and ranks and split and recombined the columns. In the movie, O Brother,

Where Art Thou? there was a scene where the Ku

Klux Klan marched before a flaming cross at

night. It was like that, only done by women and children in a big hall.

Fraternal

orders were big then. Mother had signed us up for the Woodmen of the

World. It

was like an insurance company. You paid your dues and had a small

insurance

policy in your name. You also went to a meeting hall and wore a cap

like a

soldier’s cap and marched to the music. A woman had a clapper made from

four

castanets on a stick and kept time even when there was no music. I

still

remember the marches, All American

Promenade, Over the

Waves and some Souza

marches that were played on a 78 rpm record player. We marched in

patterns of

columns and ranks and split and recombined the columns. In the movie, O Brother,

Where Art Thou? there was a scene where the Ku

Klux Klan marched before a flaming cross at

night. It was like that, only done by women and children in a big hall.

I had other

influences at that time. My mother was a Mormon, descended from

pioneers who

crossed the western plains to Utah and on to Arizona. My father was not

a

member but I attended Church and Sunday school on Sunday, and Primary

on

Tuesday after school. I learned to give short talks to my peers and had

a

circle of friends there that did not necessarily correspond to the

friends in

my neighborhood or at school. Mormons were a very small subset of the

El Paso

community and so I had very compartmentalized sets of friends.

My Uncle

Fred had just married and was the age to go into the military. When you

were

called then it could have been to any branch of the service. It would

seem

unlikely that anyone from El Paso would be called into the Navy.

Ninety-nine

percent of young men in El Paso have never seen any body of water

larger than

the pool at the Y, much less an ocean. Nevertheless, Uncle Fred became

a Seabee

or, as the name suggested, a member of a Construction Battalion, C-B.

His

specialty was refrigeration and that would become his occupation for

the rest

of his life. His location would be secret. There were lots of secrets

about the

war. “Sh! Loose Lips Sink Ships” was the motto. The family wanted to

know where

he was going so they assumed the Pacific region and made up girls names

for

every island they could think of. So when he asked about someone not in

the

family we would have a clue where he was. When he wrote about something

between

two strange girls we suspected it was Midway Island; which was one of

the islands

that did not get a name. Now we could listen to the news with some

understanding of his risk.

My Uncle

Fred had just married and was the age to go into the military. When you

were

called then it could have been to any branch of the service. It would

seem

unlikely that anyone from El Paso would be called into the Navy.

Ninety-nine

percent of young men in El Paso have never seen any body of water

larger than

the pool at the Y, much less an ocean. Nevertheless, Uncle Fred became

a Seabee

or, as the name suggested, a member of a Construction Battalion, C-B.

His

specialty was refrigeration and that would become his occupation for

the rest

of his life. His location would be secret. There were lots of secrets

about the

war. “Sh! Loose Lips Sink Ships” was the motto. The family wanted to

know where

he was going so they assumed the Pacific region and made up girls names

for

every island they could think of. So when he asked about someone not in

the

family we would have a clue where he was. When he wrote about something

between

two strange girls we suspected it was Midway Island; which was one of

the islands

that did not get a name. Now we could listen to the news with some

understanding of his risk.

Things

were

getting scarce and even postal letters were involved. The government

invented

V-mail. Now you know how email became instantly accepted as a moniker

for the

new technology. The V stood for victory and became attached to

everything to

remind us of our priorities. V-mail was a method for taking hundreds of

pounds

of precious cargo space and compacting it on a roll of microfilm for

the trip

and printing it out at the destination for distribution. Everyone wrote

a one

page message on a large sheet of paper which was sorted and filmed for

each

destination and then printed half size before delivery at the other

end. If

both parties wrote every day then both parties might receive mail in

batches of

14 every two weeks. I think everyone including the censors read

everything

several times and pretty soon the same jokes would show up all over the

place

in V-mail. The address and the message were on the same side of the

paper like

a postcard, so anyone that handled it could see it. The little teeny

envelope

was not used until it was at its destination. You could buy preprinted

greeting

cards on V-mail blanks so all the person had to do was address it. Some

people

drew pictures and cartoons. That’s when we learned about Kilroy, the

little guy

peeking over the fence. ‘Kilroy was Here’ began popping up all over the

place.

Before that, the only universal graffiti I could remember was a

stenciled sign

spray painted on every building, alley, and wall where cars would be

that said,

‘Watch the Fords go by’. The words go and by were very close to each

other and

I assumed ‘goby’ was a word I had not learned yet. Of course the word

Ford was

in the trademark font on the radiator caps of all Fords at the time.

Ford got a

lot of cheap advertising in those years. The only other thing that came

close

was the Burma Shave signs along the road set out as a rhyming series of

clever

signs to break up the monotony of a long drive. Here is an example: Henry The

Eighth - Sure Had Troubles - Short On Wives - Long On Stubble! -

Burma Shave.

Things

were

getting scarce and even postal letters were involved. The government

invented

V-mail. Now you know how email became instantly accepted as a moniker

for the

new technology. The V stood for victory and became attached to

everything to

remind us of our priorities. V-mail was a method for taking hundreds of

pounds

of precious cargo space and compacting it on a roll of microfilm for

the trip

and printing it out at the destination for distribution. Everyone wrote

a one

page message on a large sheet of paper which was sorted and filmed for

each

destination and then printed half size before delivery at the other

end. If

both parties wrote every day then both parties might receive mail in

batches of

14 every two weeks. I think everyone including the censors read

everything

several times and pretty soon the same jokes would show up all over the

place

in V-mail. The address and the message were on the same side of the

paper like

a postcard, so anyone that handled it could see it. The little teeny

envelope

was not used until it was at its destination. You could buy preprinted

greeting

cards on V-mail blanks so all the person had to do was address it. Some

people

drew pictures and cartoons. That’s when we learned about Kilroy, the

little guy

peeking over the fence. ‘Kilroy was Here’ began popping up all over the

place.

Before that, the only universal graffiti I could remember was a

stenciled sign

spray painted on every building, alley, and wall where cars would be

that said,

‘Watch the Fords go by’. The words go and by were very close to each

other and

I assumed ‘goby’ was a word I had not learned yet. Of course the word

Ford was

in the trademark font on the radiator caps of all Fords at the time.

Ford got a

lot of cheap advertising in those years. The only other thing that came

close

was the Burma Shave signs along the road set out as a rhyming series of

clever

signs to break up the monotony of a long drive. Here is an example: Henry The

Eighth - Sure Had Troubles - Short On Wives - Long On Stubble! -

Burma Shave.

I think

some people may have made up their own versions. Some of the signs did

not end

with Burma Shave. That was the clue. Even when it was missing, you

would just

say ‘Burma Shave’ to yourself. Before billboards there were barns. An

unpainted

barn could last a little longer with a tobacco or snuff ad painted on

the side.

I had an

early experience on what it was to be a boy. My mother became concerned

that I

would not learn to keep my foreskin clean and explained that she

thought it

ought to be cut off. The thought horrified me. I was becoming aware

that those

were my private parts and didn’t want anyone messing around in that

area. I was

five and having problems with sore throats so it was decided that I

would have

my tonsils out. And my adenoids. And maybe the foreskin thing. I was

worried. I

requested just the tonsils and adenoids, please, and promise you won’t

touch

anything else. I was confident when they put the ether cup over my face

that I

was safe. The anesthesia was a real thrill. I remember seeing a great

fireworks

show and hearing heavenly music like the Mormon Tabernacle Choir

hitting a

major chord. Years later I would discover the joys of nitrous oxide and

remember the same feeling. It was happy going in.

I

was

betrayed! When I woke up I had pain at both ends. I had been

circumcised

against my will. I was not impressed by the Jell-O and ice cream that

was

promised to ease my throat. I had been violated and amputated and I

didn’t know

what residual damage existed or how long it would take to stop hurting.

How was

I going to pee? The indignity of having a bandage at my crotch and

having to be

attended at every urination was devastating. The whole world knew. It

might

have been okay to have stayed in the house, but I had to go out in the

car to

visit my mother’s friends. I think I kept my eyes shut all the time. I

eventually healed. To a five-year-old it seemed like a whole lifetime.

Eventually I would come to accept the new shape and show it off to

anyone who

seemed interested. And that became a problem.

I

was

betrayed! When I woke up I had pain at both ends. I had been

circumcised

against my will. I was not impressed by the Jell-O and ice cream that

was

promised to ease my throat. I had been violated and amputated and I

didn’t know

what residual damage existed or how long it would take to stop hurting.

How was

I going to pee? The indignity of having a bandage at my crotch and

having to be

attended at every urination was devastating. The whole world knew. It

might

have been okay to have stayed in the house, but I had to go out in the

car to

visit my mother’s friends. I think I kept my eyes shut all the time. I

eventually healed. To a five-year-old it seemed like a whole lifetime.

Eventually I would come to accept the new shape and show it off to

anyone who

seemed interested. And that became a problem.

I think I

must have been born with the knowledge of sex. It became important to

learn

some new nouns and verbs to become proficient in the subject and these

were

supplied by some older boys in the neighborhood. For some reason my

parents did

not seem willing to facilitate my education in this area and would

respond with

definitions of nice boys and warnings of being shunned by nice people.

So, it

became a secret compartment in my mind. I thought about it all the

time. It

became the foundation for guilt. I learned not to say certain words. I

was

worried that even if I said them privately they would be so easy to say

that

they would just pop out of my mouth at the wrong time. I did try them

out on a

typewriter in the house to see how they worked in correspondence. I

boasted to

an imaginary friend of my conquests and accomplishments. They looked

kind of

exciting on paper but I was careless and the wrong person saw them. I

wouldn’t

make that mistake again. It also curtailed my literary development

since I was

not allowed to touch the typewriter again until I was in high school.

I

knew

about girls, too. Our next-door neighbors had twin girls born four days

after

me. Birth mothers stayed in the hospital for about a week in those days

and the

twins did not have enough milk from their own mother so volunteers were

asked

to express milk and donate to the cause. So, we were not bosom buddies

but we

started out on the same mother’s milk. I did have bath tub experiences

with the

twins and knew their genitals did not resemble mine at all; which

became a

fascination. By the time I was five I had figured all about sex. I had

a very

startling dream in which I saw up one of the twins dress and there were

genitals just like mine. That dream stayed etched in my mind for the

rest of my

life. A few years later, I had a dream where Porky Pig was standing

behind me

in the grocery store and it gave me some comfort that dreams did not

necessarily express reality. Many years later I would question the

fuzziness of

reality. Thirty five years later I would meet Mel Blanc face to face

and he

would talk like Porky Pig and that time it was real.

I

knew

about girls, too. Our next-door neighbors had twin girls born four days

after

me. Birth mothers stayed in the hospital for about a week in those days

and the

twins did not have enough milk from their own mother so volunteers were

asked

to express milk and donate to the cause. So, we were not bosom buddies

but we

started out on the same mother’s milk. I did have bath tub experiences

with the

twins and knew their genitals did not resemble mine at all; which

became a

fascination. By the time I was five I had figured all about sex. I had

a very

startling dream in which I saw up one of the twins dress and there were

genitals just like mine. That dream stayed etched in my mind for the

rest of my

life. A few years later, I had a dream where Porky Pig was standing

behind me

in the grocery store and it gave me some comfort that dreams did not

necessarily express reality. Many years later I would question the

fuzziness of

reality. Thirty five years later I would meet Mel Blanc face to face

and he

would talk like Porky Pig and that time it was real.

Thoughts of

war were everywhere. Movies were a very important common experience for

Americans. Movies were cheap and were the source of our wartime

propaganda. We

always started with the national anthem and newsreels along with the

movie and

cartoon and serialized superhero short. It didn’t take long to

incorporate

Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo into the animated cartoons. They were

clowns to be

humiliated by the likes of Popeye and Daffy Duck. Cartoon dogfights

took place

to illustrate how the USA could whip those Japs; and the kids would

cheer. WW2

was a very popular war.

We saved

everything for defense; balls of string, balls of tinfoil (there was no

aluminum foil), and even grease from cooking. Anything could be used to

make

weapons. When word got out that spider webs were being used to make

crosshairs

for bombsights, we almost collected cobwebs but could not find anywhere

to take

them.

I saved my

pennies to buy airplane spotter manuals. Next to a Boy Scout manual,

there

couldn’t be a more valuable reference book. I really needed to know the

good

guys from the bad. Who knows when a Japanese Zero would fly over El

Paso? They

flew over Honolulu, didn’t they? It was then that Mitsubishi came into

my

vocabulary. For many years, most Japanese manufacturers chose an alias

for

their company name like Panasonic for Matsuchita.

Rationing

was very prevalent, starting with gasoline and going on to sugar, meat,

coffee,

and butter. It became more important than money. People were robbed for

their

ration books and they felt devastated beyond any monetary loss. After

all, you

can get more money. The books were about 2 by 5 inches and about ten

pages at a

time. Each page had perforated panels like stamps with symbols of

tanks, guns,

and airplanes on each stamp. The stamps would expire so you had to use

them in

the time period that they were valid. The stores would have a sign

indicating

which stamps were valid. If you didn’t actually buy the food in the

time period

it was too bad. Short-term cash problems could cause a great

inconvenience and

you could not easily plan ahead because sometimes the stamps were used

in a

random manner. It was illegal to sell stamps. Butchers could sell a

single

piece of baloney and so he had to also make change for the ration

stamp. This

was in the form of red and blue tokens; which did not expire. Using too

many

tokens raised eyebrows and you might be considered unpatriotic to be

guilty of

hoarding your privileges. Then margarine became popular. To make sure

no one

was counterfeiting butter, the only margarine you could buy was pure

white and

also contained a color envelope so you could dye it yellow after you

got home.

Being caught transporting colored margarine was a very serious crime.

Some

families, like mine, learned to eat white margarine because it was more

convenient. You had to soften it, color it and re-refrigerate it before

eating,

otherwise.

Sugar was

in short supply and so home canning became a problem. We were fortunate

that we

lived on the Mexican border. I can remember going across the bridge to

Juarez

to buy sugar. We had to park on the US side and walk to the store, then

return

carrying a five-pound bag for each person in the group. When the

customs

inspector came around to check our haul, there had to be a warm body to

represent each bag of sugar we had. I think there was a period of time

involved

or maybe the custom agent took a ration stamp. Anyway, sugar was a

scarce item,

so they invented saccharine and lots of people used it, but didn’t

really like

it. If you said someone was saccharine, it wasn’t a compliment; it

meant phony,

not sweet. Coffee was not a big problem for our family, but something

we took

advantage of it in the Mexican market. It could be traded or we could

use it

for our friends who drank it. It is a curious thing that we could go to

a poor

country to get luxury items in wartime. Could it be that scarcity of

goods is

more related to team building than inability to provide? There goes my

fuzzy

reality again.

You hear

stories about ladies stockings and how women learned to mend them using

tiny

hooks to loop around the runs. My mother bought one. I have seen women

taking

their stockings to Kress’s department store to be mended while they

waited. The

women wanted to wait for fear they would never see their stockings

again, so

they were willing to stand in lines. Standing in lines seemed to be the

only

solution for a lot of things.

Later, when

the war ended, I became aware of who had to stand in lines and why.

People

stand in lines for entertainment and sports and seem to have a good

time of it;

but to have to stand in line for the necessities is inhumane. I always

felt

sorry for the East Europeans and Soviets for their grim queues and for

their

interpersonal conflict in line. It is a symbol of the good life to

never have

to stand in line for necessities.

One of the

things that happened at a tender age that affected me all my life

concerned

Christmas. I had expressed a desire to have a 16 mm movie film

projector and

was told that it was not likely that such an expensive item would be

available.

Some time later it was noted that my father needed new underwear. The

night

before Christmas Eve we all went downtown and drove around the block

while my

mother went in to a department store. She came out with a package that

went

into the trunk and the comment was made about getting underwear for

Dad. On

Christmas morning I got my projector but there was no underwear for

Dad. I

learned something about Christmas that year about Santa and sacrifice,

but

mostly about guilt. I still get angry about the commercialization of

such a

serious commemorative. As I learned Latin and Roman History and learned

about

the hijacking of the Christian faith and traditions, it just added to

my

dissatisfaction of our current practices. How do we expect children to

accept

the seriousness of the atonement of Jesus Christ when we fill their

heads with

Santa, flying reindeer, Easter bunnies, and other lies?